Do psychedelics make you liberal? Not always

I’m doing a talk on this topic at the Psychedelic Society UK, online, on March 3.

When it emerged that the ‘Qanon shaman’, Jake Angeli, was not only the poster-boy for the Trumpist insurrection, but also a vocal promoter of psychedelic therapy, it provoked consternation among the psychedelic community. How could a psychonaut support Trump, and fall for an authoritarian and quasi-fascist conspiracy theory like Qanon?

The disbelief stemmed from a widespread conviction — and some evidence — that psychedelics make you more liberal, more open-minded, more connected, more ‘relaxed in your beliefs’, and less prone to authoritarian thinking, extremism or political polarization.

Clearly, that is sometimes the case, but not always. It does not same to have happened with Jake. He appears to be extremely polarized in his political thinking, dividing the world into heroic light-workers and demonic villains. He’s a proud Trump-supporting, gun-owning, ex-military conspiracy-theorist, and he’s into psychedelics. Is he an anomaly?

Not at all. A brief look at psychedelic history shows psychedelic practitioners have often been conservative, traditionalist supporters of elitist hierarchies. I am drawing here on my own research, and also that of Alan Piper and Gary Lachmann.

First, we can note that Meso-American cultures, which used psychedelics as part of their ritual religion, did not become liberal after taking mushrooms. The Aztecs used magic mushrooms as a means to connect to their gods, but remained very fond of human sacrifice. It’s estimated that in four days, during the re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitian in 1487, Aztec priests sacrificed between 10,000 and 80,000 men, women and children. Aztecs had different sacrificial rituals for every month — July was sacrifice by starvation, while in August a young woman was sacrificed, flayed, and her skin worn as a costume. The endless bloody sacrifices were means of perpetuating the pyramidal hierarchy of Aztec society — at the top, the gods, then the semi-divine emperor, then the warrior-elite and priest-elite, then women, and at the bottom, those in debt or captured outsiders.

The ceremonies were certainly ‘heart-opening’, though in a different sense to today’s hippy terminology — Bernal Diaz writes:

They strike open the wretched Indian’s chest with flint knives and hastily tear out the palpitating heart which, with the blood, they present to the idols … They cut off the arms, thighs and head, eating the arms and thighs at ceremonial banquets. The head they hang up on a beam, and the body is … given to the beasts of prey.

Contemporary Amazon shamanism is, of course, slightly less organized in its violence. But you would still struggle to call the world of Amazon shamanism ‘liberal’ or ‘progressive’. Rather, Amazon indigenous cultures can be highly patriarchal, heteronormative and conservative. To live well is to live in static harmony with the land, your tribe, your ancestors and the spirit world. Amazon shamanism can also be rather violent — there is an entire form of magic known as ‘battle magic’, in which shamans try to kill each other to prove their superiority and steal their foes’ spirit-allies. Amazon shamanic culture is not always a culture of emotional openness and sharing, but has been described as a culture of suspicion and vengeance — its model of medicine is based on the idea that illness and misfortune are caused by curses. Psychedelics help you discover who has cursed you and get revenge.

Turning to the psychedelic roots of western culture, let’s assume for the moment that the ancient mystery rites of Eleusis, in Greece, involved the ingestion of psychedelic drugs. In some ways, the ritual has good liberal credentials — it helped to nourish the earliest democracies in the history of humanity. The mysteries brought together Greeks from all the different Greek city-states, and gave them a shared experience of eunoia (fellow-feeling, the opposite of paranoia). One could go so far as to speculate that the philosophical idea of the ‘brotherhood of man’ — first expressed in Stoic philosophy — has its roots in the psychedelic experience of Eleusis.

At the same time, Eleusis was a very traditionalist cult, based on the same fundamental idea as the Aztec human sacrifices — humans depend on the good favour of the gods, and we must perform rituals to placate the gods, or they will punish us. This idea naturally empowered and enriched a priest-class — Eleusis was an extremely well-funded ritual. It was also strictly policed — the penalty for revealing its secrets or in some way blaspheming against it was exile or death. And, like the Aztec psychedelic rituals, it ‘probably involved human sacrifice…pacified in the later evolution [pf the rites] by the offering of animal surrogates’ — so suggests Carl Ruck, who first put forward the theory Eleusis involved psychedelics.

Leaping several centuries and turning to the rediscovery of psychedelics in western culture at the end of the 19th century, we note that the early pioneers of psychedelic research tended to be elitist, authoritarian men.

One of the first ever research papers on psychedelics was by Havelock Ellis, the British medical researcher, who wrote Mescal: A New Artificial Paradise in 1898. He describes peyote as ‘the most democratic of the plants which lead men to an artificial paradise’, because of the ‘halo of beauty it casts around the simplest and commonest things’. However, Ellis was not entirely democratic in his own politics — he also wrote The Sterilization of the Unfit, in which he argued that thousands of humans at the bottom of the social pyramid should be sterilized for the good of the Race. There is a connection between this elitism and his view of psychedelics — he thought they were only suitable for civilized healthy people, in other words, the cognitive elite at the top of the pyramid.

One of Ellis’ charming odes to sterilization — he balked at involuntary sterilization but thought it could be tied to welfare payments.

Ellis expanded his research by giving mescaline to two of his friends — the poet WB Yeats and the literary critic Arthur Symons. Yeats was even more elitist than Ellis. In 1939, at the end of his life, he gave his firm support to the brutal eugenic policies being carried out by the German and American governments. ‘Sooner or later we must limit the families of the unintelligent classes’, he wrote. He thought civilization depended on a handful of elite families, who may have to seize military control of society to enforce eugenic policies on the masses.

Yeats was a member of the elitist Order of the Golden Dawn, along with Aleister Crowley — another early experimenter with psychedelic drugs. Crowley’s use of peyote does not seem to have made him liberal. Rather, he shared Yeats and Ellis’ highly hierarchical, pyramidal view of society — he believed a new aeon was dawning in which a handful of Nietzschean supermen would rule over the ‘slaves’ of the masses. They must rule pitilessly: ‘Compassion is the vice of kings. Stamp down the wretched and the weak.’

I should mention here, in passing, the work of Richard M. Bucke, not because he ever took psychedelics, but because his book Cosmic Consciousness (1901) was so influential for later psychedelic culture. Bucke thought some humans attain a mystical experience of cosmic oneness, and he attempted a scientific account of this, which influenced his friend William James and later researchers like Timothy Leary. But his account is, again, profoundly imbued with elitism.

Bucke basically thought he and his friends had, by having this cosmic oneness experience, ascended to the next sung on the evolutionary ladder, and become supermen, destined to surpass the human race and rule the world. He also thought many humans and some ethnic groups were incapable of attaining this higher level of consciousness, and should be separated and possibly sterilized for their own good, and the good of the species.

We also note that the government which embraced psychedelic research most eagerly, before Donald Trump, was Nazi Germany. The Nazis funded research into psychoactive drugs for two purposes — firstly, to try and enhance human potential and create superhumans, capable of enduring hostile conditions while performing at a high level; secondly, to break open people’s minds and make them easy to control. For the first aim, they gave methamphetamine pills to their front-line soldiers to aid them in the Blitzkrieg that conquered western Europe in a matter of weeks. For the second aim, they forcibly injected mescaline into Jewish prisoners in concentration camps, to see if it could be used as a truth-drug.

These experiments were carried on, after the war, by the CIA in their notorious MK Ultra programme. The CIA recruited Nazi scientists to continue experimenting with psychedelic drugs, to try and break down conditioning and create minds susceptible to brain-washing.

The first era of psychedelic research, therefore, was typified by deep attitudes of elitism, spiritual inflation, authoritarianism and eugenics — typical attitudes for Modernist intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century. And this Modernist intellectual elitism carried on into the golden age of psychedelic research, in the 1950s.

The most famous psychedelic researcher in the 1950s, besides Albert Hoffman, is Aldous Huxley, in many ways a typical Modernist elitist who believed the human race was degenerating intellectually, because the mentally unfit were outbreeding the fit. In order to develop humanity’s potential, it was necessary for the elite (people like him) to develop their potentialities using spiritual techniques, including psychedelics, and also to control the masses using eugenics. He argued this stridently in the 1920s and 30s, less so after the war but he would still voice support for eugenics right up to his death. His last novel, Island, is in no sense a liberal utopia. It’s a highly conservative society in which things never change — in this respect it’s the mirror of Brave New World, the supposed ‘dystopia’ Huxley wrote 30 years earlier.

Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy (1946) is a foundational document for western psychedelic culture (Nicolas Stanglitz has written of the ‘acid perennialism’ one often finds in psychedelic culture). It’s one of my favourite books, but it’s essentially a conservative book — there is a core of wisdom in all spiritual traditions, which humans must absorb. There is one right way to live, one divine goal, and society should be structured to serve this theocratic goal. It’s not quite as authoritarian as his fellow perennialist Julius Evola, but it’s certainly conservative.

One of Huxley’s closest friends and co-experimenter with psychedelics was Gerald Heard, the British writer and mystical seeker. Heard was responsible for first introducing psychedelics to the business elite of Silicon Valley. He believed that humans were spiritually evolving, and that some humans were attaining ‘superconsciousness’, and at times he suggested these superbeings should rule society as a ‘neo-Brahmin’ caste. He seemed to have associated this neo-Brahman caste with the business elite — he gave psychedelics to business tycoons like the CEOs of Time-Life and the Southern Electric Edison Company.

Huxley and Heard passed the baton of psychedelic research to Timothy Leary, who took a more democratic approach to it. Rather than their strategy of ‘give psychedelics to the cultural and business elite’, Leary suggested psychedelics should be given to everyone. But he still inherited some of the elitism of the earlier generation of researchers. Kids who take psychedelics are the initiates, the ‘experienced ones’, the ‘new race of mutants’ who will take humanity up to the next rung of evolution. Squares, meanwhile, ie the non-initiated, are fated to be left behind. Ken Kesey likewise thought of him and his Merry Pranksters as evolutionary superheroes.

There is a vein of Gnostic narcissism in Sixties psychedelic culture — we are the turned on, the special ones, the children of Light, the Beautiful People. Everyone else is square, dead, unreal, pigs — they barely deserve to exist. You can see how this antinomian narcissist elitism could morph into authoritarian homicidal psychedelic cults like the Manson Family, or Osho’s cult in Oregon, both of which used psychedelic drugs to instil devotion in its members.

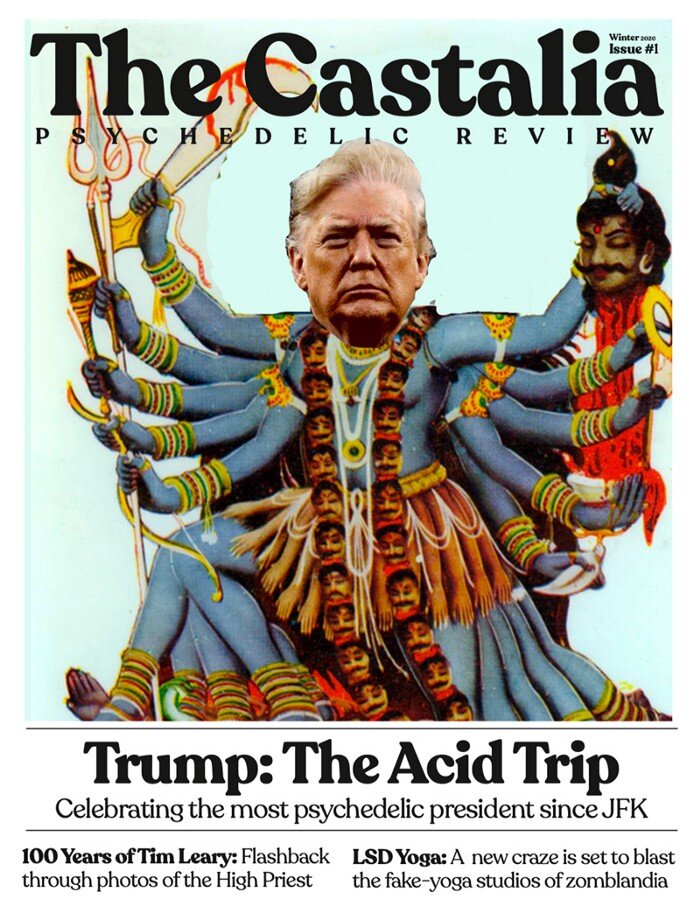

So now we have the psychedelic renaissance, and the firm hope that psychedelics will make us liberal, progressive, globalist environmentalists. Maybe. At the same time, it’s been noted that two of the biggest funders of the present wave of research were also leading funders of the Trump 2016 campaign — Peter Thiel, a libertarian who supports Seasteading (ie entrepreneurs setting up their own Huxley-esque autonomous islands), and Rebecca Mercer, who funded the far-right Breitbart news agency. Donald Trump was also a firm supporter of psychedelic therapy, intervening to green-light ketamine therapy for veterans (at Rebecca Mercer’s request). He’s been called ‘the most psychedelic president’, probably fairly, by the Castalia Foundation — a right-wing contemporary psychedelic organisation.

Californian spirituality is not necessarily social democratic. It also has a strain of right-wing libertarianism and Nietzchean anti-democratic elitism. And the psychedelic market is shaping up to cater to this demographic — psychedelics are sometimes sold as a means for the global business elite to optimize themselves.

At the same time, some psychedelic practitioners and communities have fallen prey to ‘conspirituality’ — to the paranoid Gnostic sense that the world is being controlled by an evil globalist elite. Alan Piper has explored how psychedelics have long been popular with neo-Pagan war-glorifying nationalist and fascist groups (see also this recent article from Psymposia), and Jake Angeli (the Qanon shaman) could be placed within this subculture (in some far as he’s a pagan warrior-worshipping Trump-supporting ex-veteran).

This is a different sort of right-wing psychedelic ethos — not elitist, exactly, so much as anti-globalist, anti-elitist. At the same time, it has a similar sort of spiritual narcissism (‘I am one of the special awakened ones’)…but it probably appeals more to less wealthy, less educated, less connected and more disenfranchised people like Jake. It’s an outsider ethos, as opposed to the insider ethos of people like Aldous Huxley.

That’s a brief survey to show some of the ways psychedelic culture has skewed towards elitist and authoritarian forms of politics in the past. I’m not arguing that psychedelic politics is always elitist and authoritarian, just that it’s not always liberal and progressive either. Psychedelics often act as culture-amplifiers, enhancing a person’s personality traits. There are instances where psychedelics have transformed a person from a violent authoritarian mind-set — I think of how MDMA changed some football hooligans to peace-and-love ravers in the late 1980s — but there are other cases when it seems to have enhanced this mind-set.

What can psychedelic culture do to protect itself against the tendency to spiritual elitism and spiritual inflation? Perhaps at least remind ourselves, continuously, of this historical bias in our culture, and try to notice it in ourselves, and remind ourselves that, even if we have achieved ego-death and conversed with DMT elves, our shit still smells like everyone else’s.

One could, finally, make an argument for a more centrist form of psychedelic conservatism. One could argue that psychedelic culture fits very well with a sort of Burkean conservatism, which values cultural traditions and promotes virtues like self-control, concentration, respect for ancestors, healing for veterans, and a sacred sense of connection to the land and nature. In a way, Michael Pollan in his best-seller How To Change Your Mind, reframes psychedelics in this way — not as counter-cultural, but rather as pro-cultural, as an initiation into your culture’s deepest sacred traditions.

I’m not saying you have to see psychedelics in that way. But it’s worth considering that psychedelic culture may actually be more conservative (with a small c) than it realizes. And that one might want to make this case, if one seeks to persuade right-wing politicians of the benefits of legalizing psychedelics.

I’m doing a talk on this topic at the Psychedelic Society UK, online, on March 3.