The Neuroscience of Enlightenment

The neuroscience of enlightenment

For some, the word enlightenment brings to mind the European “Age of Reason” and the 17th-century origins of science. For others, it evokes the transcendence of self and suffering described by multiple Asian religions. Today, these two traditions have finally met, in the scientific study of meditative and psychedelic states. Most of this research has focused on health and productivity benefits, but these states are also capable of providing profound insight into the nature of the mind and even the total transcendence of suffering. In spite of the research bias away from these topics, we are now beginning to get insight into what happens in the brain during states of enlightenment.

What is enlightenment?

At its core, the enlightened state is synonymous with liberation from suffering. The term “moksha” in Hinduism captures this idea of being released into a state of absolute freedom. Freedom from a deluded way of seeing the world. By framing enlightenment in terms of psychology we can move away from potentially supernatural claims and towards a naturalistic understanding of how suffering works and how we can overcome it. With the advent of more scientific research into the effects of meditation on the brains of long-term meditators, the idea of enlightenment is becoming less and less taboo in scientific circles.

Viewing enlightenment through this psychological lens, we can see that in normal waking consciousness we don’t typically see reality clearly, and as a result, we suffer. This gives rise to the idea of enlightenment as “awakening” from this deluded state--the Buddha means “the one who woke up”. What is at the core of this delusion? One could argue that it is the perception of the world and the mind as being divided into separate objects. When conceptual divisions are seen for what they are, as concepts rather than objective categories, what’s left is the perception of a perfectly unified reality. Often the most challenging conceptual division to see through is between “self” and “world”. When this division collapses, one experiences what might be called ego-death or ego-dissolution. In the modern world, this is a major route into the liberated enlightened state, particularly when it comes to the use of psychedelics.

Mindfulness & the gradual approach

One way to approach the enlightened state is to cultivate it gradually. The Buddha taught that it is our clinging to aspects of reality that causes suffering. We want things to be and remain a certain way. We want the world to be made up of reliable, unchanging objects and so we sort the world into these kinds of conceptual categories. When reality inevitably changes we suffer because we have a goal that is counter to the nature of reality. If you cling to an image of yourself as youthful, for example, you will suffer psychologically when you inevitably age. In the gradual path, one practices letting go of clinging through meditation. What happens in the brains of experts who have deeply cultivated non-attachment of this kind?

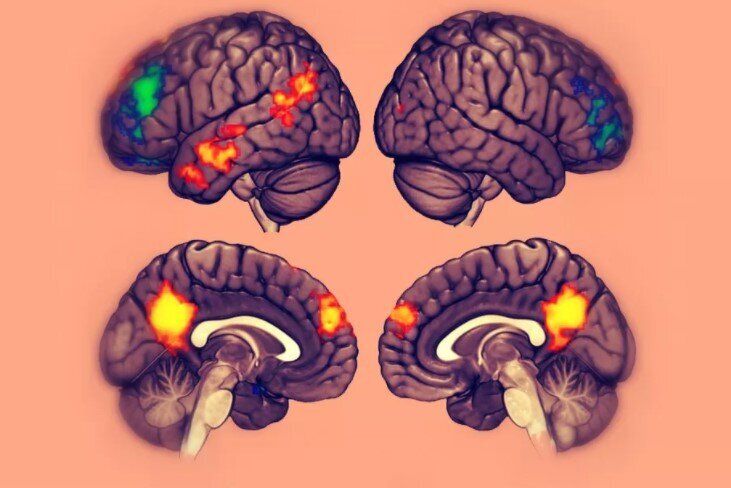

Mindfulness refers to a state of non-judgmental present moment awareness, a way of being with non-clinging at its core. When the state of the brain is investigated using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) during mindfulness meditation, increased activity is consistently observed in two particular brain areas. One is the prefrontal cortex, located on the surface of the brain, just behind your forehead. The other is the anterior cingulate cortex. The cingulate cortex is a strip of brain tissue that runs front-to-back and sits in the center of the brain, where the two hemispheres face each other. The anterior cingulate cortex is the portion at the front, towards the eyes. Both of these areas are known from other studies to be involved in the regulation of attention. Given the training in the control of attention that comes with the practice of meditation, increased activation of these areas during meditation is hardly a surprise. Similarly, an increase in slow alpha oscillations, waves of electrical activity that repeat around 10 times a second, is observed during meditation and is thought to be related to attention. These findings tell us about the attentional skills cultivated by meditators but they do not give us real insight into the physiological basis of the enlightened state.

MRI anterior cingulate

Mind-wandering & the Default Mode Network

When one is not meditating, the mind tends to wander. In our typical way of being we might think about what we did yesterday and what we plan to do tomorrow. Notice that both of these kinds of thoughts are about what “you” did and will do. They refer to your “self”. Our everyday experience of the world is filtered through this self-referential process of mind-wandering. When we are lost in thought in this way, our thoughts weave together a mirage of a solid self that exists over time. In such moments, we typically don’t recognise the self for the illusion that it is. Seeing through this conceptual division between what is “you” and what is not “you” can give rise to liberated states of enlightenment, both through meditation and through the use of psychedelics.

Scientists have discovered that if you let someone’s mind wander while scanning their brain, you see a constellation of brain areas that become active together. There are three brain areas that form the core of this network. One is the medial prefrontal cortex, a region of the part of the brain behind your forehead that we met earlier. Instead of sitting on the surface directly under the skull, however, it sits on the side of the brain where the two hemispheres meet, in the same way as the cingulate cortex that we also met earlier. The posterior cingulate cortex, located behind the anterior cingulate cortex, is another key area of this network. Finally there is the angular gyrus, a bump of brain tissue that sits just above your ears. This network is active when you’re in your everyday, default way of being. As a result, it is known as the default mode network (DMN).

MRI of posterior cingulate

Psychedelic ego-dissolution

When we meditate or take psychedelics, we are no longer in our default mode. We may even totally see through the conceptual division of self and other that is thought to be mediated through the activity of the DMN. What happens to the DMN during meditation? When meditation consists of focussed attention on an object like the breath, reductions in the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex are observed. This fits with the idea of this form of meditation practice as a route to enlightenment through self transcendence. As DMN activity quiets we are less focused on activity constructing a psychological concept of self, allowing this suffering-generating division to be overcome or transcended.

The idea of enlightenment states being reached through psychological self-transcendence associated with decreased DMN activity is supported by studies with psychedelics. High doses of classical psychedelics like psilocybin have been found to reduce brain activity in both the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex during experiences of ego-dissolution. The forced dissolving of the boundary between self and world routinely produces unitive, mystical, enlightenment-type experiences of liberation. Since we know that serotonergic psychedelics exert their effects by a acting on a particular serotonin receptor that is concentrated in these nodes of the DMN, the 2A receptor, these effects provide causal evidence for the involvement of DMN suppression in experiences of self-transcendence. Without the research on psychedelics, we might be limited to just studying the correlation of brain states with these experiences during meditation.

The non-dual approach

The DMN isn’t the only network of brain areas that underpin our everyday experience of the world. There is also what has been termed the task-positive network (TPN), a collection of connected brain areas that are recruited when our attention is outwardly focused. These activity patterns of the TPN and DMN are anti-correlated, when one goes up the other usually goes down. They are typically seen as underpinning mutually exclusive functions--either you are inwardly focused and mind wandering or you are externally focused on completing a task. These differences in attentional focus have led to these networks also being termed the intrinsic and extrinsic networks, respectively. During focussed attention meditation, not only is activity in the DMN decreased, but the anti-correlation between this network and the TPN is strengthened. This is thought to reflect the increased external focus on the object of meditation and the decrease in self-referential inward focus.

Default Mode Network

The enlightened state consists of seeing through false divisions in reality and waking up into a way of seeing in which reality is unified and there is no suffering. Since the primary division that troubles us is the one between self and world, the experience of transcending this division is also termed “non-duality”. In certain Buddhist and Hindu traditions, non-dual approaches to meditation are practiced. In these traditions, instead of gradually cultivating non-clinging, one recognises and returns to the non-dual perspective. This is a comparatively direct path in which one drops into the enlightened state in the moment, rather than attempting to achieve it at some point in the future. By studying the brains of those who are proficient in non-dual meditation, we can perhaps get the closest glimpse possible of the physiology of enlightenment.

Researcher Zoran Josipovic at New York University is leading the charge when it comes to this research. He performed a study in which he asked expert meditators from Tibetan Buddhist traditions to perform both focussed attention and non-dual meditation. He found that as with previous studies, the focussed attention meditation increased the anti-correlation between the DMN and TPN. The non-dual meditation had the opposite effect. Compared to when not meditating, these two networks that typically were mutually incompatible become more co-active. They allowed each other to coexist. This is required to reflect the all-inclusive nature of non-dual awareness, the seeing of the unity of internal and external appearances in consciousness. Josipovic has also argued that a brain area called the precuneus may play a crucial role in non-dual states. As with the medial prefrontal cortex and cingulate cortex, the precuneus is also located where the two hemispheres meet but at the back of the head. It is connected to both the TPN and DMN and so may mediate the observed changes in how these networks interact. Furthermore, the precuneus has been shown to be invloed in lucid dreaming, a state that has parallels with the awakening of the enlightened state.

Precuneus

Science & enlightenment

Liberation from suffering can be approached from multiple paths. One may cultivate non-clinging through meditation, strengthening the ability of attentional hubs in the brain to let go when attachment causes suffering. This can eventually lead to suppression of the DMN and transcendence of the conceptual division between self and world, leaving one in a liberated state. If one is in a rush, the same mechanism can be forced by a high dose of a psychedelic, when taken with the right set and setting. If one recognises the fundamentally undivided nature of experience, one can see everything, both self-referential processes and world-related processes, as parts of a single unified unfolding. In this case, the DMN and TPN may actually reconcile their conflict over inward and outward focus and leave us with the recognition that internal and external are one.

Ultimately these different approaches will all have their uses. Transient enlightenment experiences are not of lasting value if they are not integrated through a practice like meditation. Ultimately the structure of the brain is the physical trace of what we are and how we have acted in the world. It has an incredible ability to perpetually change itself and, armed with the modern synthesis of science and contemplative practice, perhaps more of us can begin to set our brains in the direction of enlightenment.